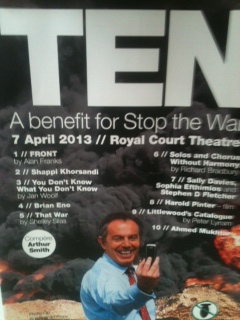

A fundraiser for Stop the War, organiser of the eve-of-operation march of February 2003 when two million people protested, it brought NW3 to SW3. Lefties including Ken Livingstone and Jeremy Corbyn MP found themselves deep behind class enemy lines. While the theatre has enjoyed an amazing bout of creative energy in the last five years – Jerusalem, Enron, Jumpy, Clybourne Park etc etc – it is still on the borders of Belgravia. “Maggie, Maggie, Maggie, Out Out Out” chanted some in the audience, little knowing that the former PM – Out for more than 20 years – would indeed be Out for good the following morning. Being a vehement Thatcher detractor must be like being someone who was dumped two decades ago, but is still obsessing over their lost love. Isn’t it all a bit of a waste of life and time and energy? Surely, it’s time to, er, move on? As Ian McEwan has noted in the Guardian, ‘We liked disliking her.’

What Ten highlighted is that the political right of centre doesn’t have the monopoly on provoking division, vitriol and loathing. Ten acts, each lasting ten or so minutes, were all inspired by, or were commentaries on, the military intervention and its aftermath. With the exception of Brian Eno, little was actually said by anyone about Iraq or Iraqis. On his journey through the ancient history of Sumeria, focusing on the epic of Gilgamesh, the world’s oldest ‘book’, he reminded us that the site of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon was, post-invasion, the US military’s Camp Alpha. The mini-lecture was accompanied by images of the work of kennardphillipps. Later, there was a film of Harold Pinter reading his anti-war poetry outside a 2004 exhibition of theirs. He wasn’t so much an Angry Old Man as About to Burst into Flames Incandescent.

The evening was really concerned with the effect of Iraq on Britain, particularly creative Britain, which still has to square the circle of its support for a Blair government that delivered the country from 18 years of Thatcherism (Major didn’t count), with that government’s illegitimate and possibly illegal war of choice. At least the Falklands had conformed to the tenets of jus ad bello and there’s never been any suggestion that Baroness Thatcher should have been prosecuted in the International Criminal Court. A recurring theme concerning the Thatcher years is how divisive they were, but as Shappi Khorsandi said, she still can’t allow herself to fancy anyone who supported the Iraq intervention, while That War, a two-hander by Shelly Silas, underlined its effect on British Muslims, all too often perceived in the last decade as ‘the enemy within’.

For some of those in the Royal Court on Sunday, enemy number one wasn’t Al Qaeda, the Taliban, Saddam or the Mahdi Army. It wasn’t Thatcher or war itself. It was Tony Blair. In You Don’t Know What You Don’t Know, Timothy West’s character says when he sees the former PM’s autobiography in a book shop, he moves it to the crime section. Director Ken Loach spoke of the ‘war cabinet of criminals’, while the biggest cheer of the night came from the suggestion that one day Blair would end up in that dock in the Hague, which is where you now go when you’re charged with crimes against humanity.

Iraqi oud-player Ahmed Mukhtar finished with a song called ‘Hope’. Perhaps he wanted to inspire members of the audience to put aside their parochialism and petty posturing and take an interest in his country which their country had violently reshaped.